Blocks World

The Foundation of Artificial Intelligence

January, 2026

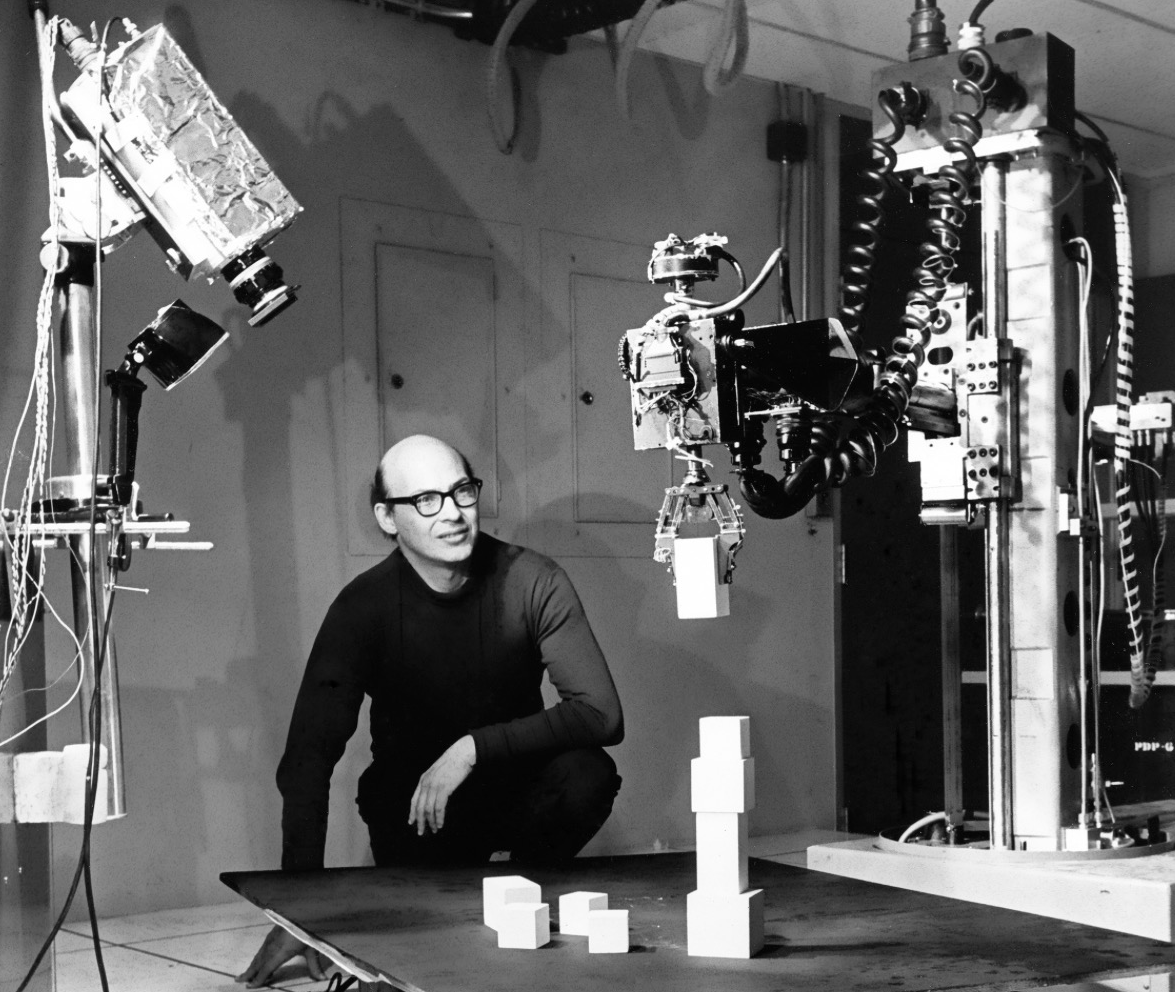

One of the earliest Artificial Intelligence challenges was to manipulate toy blocks using a robot arm. The AI lab at MIT pioneered this work starting in the late 1950s. The simplicity of Blocks World categorizes it as a "toy problem," yet even today it remains an "NP-hard"1 search-and-planning problem.

Much of Marvin Minsky's later work also originated from what the MIT team discovered in Blocks World.

"Seymour Papert and I had long desired to combine a mechanical hand, a television eye, and a computer into a robot that could build with children's blocks. It took several years...

In attempting to make our robot work, we found that many everyday problems were much more complicated than the sorts of problems, puzzles, and games adults considered hard."

—Marvin Minsky, "Society of Mind", 1986

When Terry Winograd joined the MIT AI team as a student, the team had defined Blocks World as a hand-eye coordination challenge. Terry came from a Linguistics background, and encouraged by Minsky, set out to design a Natural Language Interface to the Blocks World. His program was cleverly named "SHRDLU," inspired by hacker notation of English Letter frequency (ETAOIN SHRDLU). Aside from developing hand-eye modules, Winograd noted that manipulating objects in the Blocks World would also require a planning capability. Winograd, Eugene Charniak, and Gerry Sussman created the utility program "Micro-Planner" to fill that requirement for SHRDLU.

The Sussman Anomaly

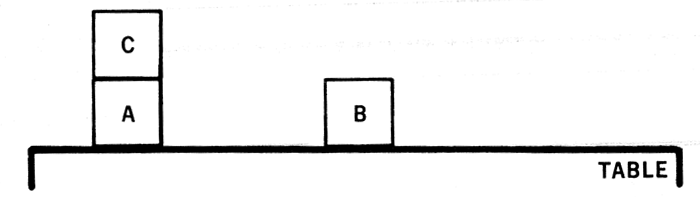

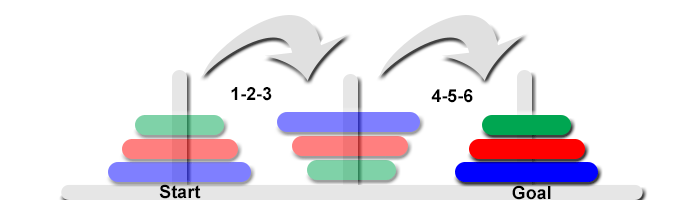

Illustration from Gerald Sussman's PhD thesis "A Computational Model of Skill Acquisition", MIT 1973

When Marvin Minsky wrote "Steps Toward Artificial Intelligence" in 1960, section IV—Planning emphasized the Identification of the problem's Goal State. If a Goal was not solvable by a known method, Sub-Goals were to be further constructed until an appropriate method was identified. Minsky and Papert would advise students in the AI Lab and help identify where meaningful work could be accomplished.

The general Blocks World scenario is that there are individually identified Blocks on a Table, and the Problem is to rearrange them from a START state to a defined GOAL state. In Sussman's example, the Goal state is a single stack of blocks in descending alphabetical order: Block C is atop Block B; Block B is atop Block A. So the Goal is C > B > A . An implicit restriction imposed by the Minsky Arm is that only one block is moved at a time.

Since C on top of B satisfies a Subgoal, that would be a constructive move. But this introduces a new problem; not being able to move B on top of A directly. If B is first placed on the stack of C > A, it satisfies the goal of B being on top of A, but with C stuck in the middle. Hence, there is an anomaly with the constructive sub-goal strategy.

Looking at the diagram, it would be OBVIOUS to us that the first move is to place C on an empty place on the table, thereby allowing the next two moves to create the desired C > B > A stack. To be fair, the planning algorithm at the time only presented a series of logical arrangements. From this, it was expected to construct a sequence of moves, based around sub-goals. The move to an empty space would require a DECONSTRUCTIVE sub-goal, novel enough within the 1973 Blocks World paradigm to earn Sussman a Ph.D. and, later, a dedicated Wikipedia page.

Elementary Blocks World

In adopting a Blocks World Puzzle for ARCHIE to solve, we will impose/modify a few conventions. First, many classic Blocks World challenges allow an unlimited table space. This allows a trivially easy strategy: Move all blocks to their own place on the table and then stack them in order. Another variation introduces different-size blocks (see photo above). For ARCHIE, we will use the same size blocks, and an intentionally restricted 'table space' to force layers of 'Deconstructive moves.' The goal is to level up the difficulty of the Tower of Hanoi puzzle previously mastered.

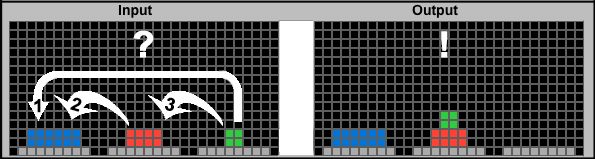

Removing the graduated sizes of the Tower puzzle may seem to make a solution easier, but combined with last move memory, the Tower puzzle has the property of being solvable from a simple "top down" rule set. Let's look at an example:

Since only one disk may be moved at a time, the Tower puzzle can be simplified by evaluating only the top disk of each stack. In the above example, all three disks need to be evaluated, along with their possible destinations. Since a larger disk cannot be placed on a smaller one, the Blue disk can be eliminated as a move candidate. Also, Red will not be placed on top of Green. A strategic rule is that a smaller disk is not moved on top of a disk an even number of positions away. This eliminates #1 (Green on top of Blue). This leaves moves #2 and #3 above. This is the trickiest situation encountered during the Tower puzzle solution process, and without any form of "memory," we would not have a definitive move.

Since we used a color shift to indicate the last disk moved (as memory), the Red disk would be Orange, and move #2 would be eliminated — since we don't move the same disk twice in a row. Green would move on top of Red (#3) as the one and only remaining move. This shows how every advance in the Tower of Hanoi puzzle is resolved by a single top-down evaluation!

What Would ARCHIE Do?

At this point in ARCHIE's development, my starting point is to make the visual examples and just see what ARCHIE tries to do with them. If a puzzle utilizes all the same concepts as other solved puzzles, ARCHIE will just solve them. Even when encountering a novel sizing and color arrangement, it is the concept, and not data, that provides ARCHIE with a solution path.

The Blocks World problem can appear similar to the Tower of Hanoi scenario, so I made similar examples. ARCHIE evaluated this as another [TOWER] puzzle and attempted to use the same method. The first two moves (stylized below) were: #1 (move Blue to an open space) and then #2 (move Red to another open space). I suspect this would be a similar reaction for a child who had previously solved a Tower of Hanoi puzzle.

A few very important things to note:

- Nothing Numeric Matches the Tower Puzzle Examples — The Tower grids are 30x15, and this grid is 24x24. The Blocks are 4 pixels high, and Tower Disks are 2 pixels high. Blocks are all the same width, unlike the defining feature of Tower Disks. The three Platforms are 4 wide and Brown, not 8 wide and Grey as with the Tower example.

- Deciding on [TOWER] was Selected from 100s of Possibilities — ARCHIE determines which OBJECTS are passive and which drive change between the Input and Output Grids. ARCHIE uses this to determine the puzzle is not a PAINT, CRAWL, EXTEND, CIPHER, LIQUID, LOGIC, MAP, MOZAIC, MAZE, or any number of other puzzle types.

- Much of the [TOWER] Action Code was Applicable — Although the Blocks are not the same as Disks, and the Goals are ultimately different, Moves #1 and #2 (above) would be valid on both Puzzle Types. During the "Iterative" multi-move process, ARCHIE got stuck at this point, since there is no "Memory" rule or "Sizing" rule to determine the next moves.

- The Conceptual Commonality is [STACK] — I had originally anticipated both a [TOWER] action and a [BLOCKS_WORLD] action. But ARCHIE's detection of the similarity helped me understand that these puzzles are really manipulating Objects arranged in [STACKS]. This new [STACK] action replaces [TOWER]. There is a branch within [STACK] that identifies the special placement rules for the Tower puzzle, versus the similar Block World variation.

Way Fewer Moves, Way Harder Method

In Illusions of Thinking, I go over the Rules for moving the Tower of Hanoi disks. Because a larger disk cannot be placed over a smaller disk, the amount of time to solve a 64 disk puzzle would "bring about the end of the Universe2."(i.e., 264-1 moves). Without this restriction, the number of moves is just 2 times the number of disks:

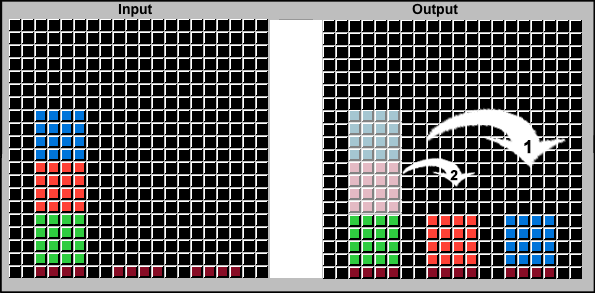

Blocks World does not have the width rule restriction and so can support a much larger initial stack. So what happens if you start with a larger stack? If Start and Goal are in the same order, the solution strategy is trivial — just invert in the middle position — no matter how many Objects have been added. So let's use the Block colors themselves to determine the final order, and start with a Stack that requires the most rearrangement. Color numbers are part of the ARC Puzzle Definition, so here is a reminder:

Each color is represented by a digit from 0 to 9.

0=Black, 1=Blue, 2=Red, 3=Green 4=Yellow

5=Grey, 6=Fuchsia, 7=Orange, 8=Teal, 9=Brown

Starting with 6 different colored blocks in a maximally difficult order, ARCHIE can use the Interave process to solve Blocks World puzzles. I have manually added numbers to the animation so you can more easily follow along. The #6 Fuchsia block needs to find its way to the bottom of the solution stack on the right. It could help if you just visually follow the progress of this block until its final placement:

Maximizing This Blocks World Challenge

The most colored blocks we can use with the ARC format are 8, since one of ten colors is used for the background and the other for the platforms. For this last example, I added an additional platform (from 3 to 4) and squashed the blocks to rectangles. ARCHIE still solves this flawlessly. It turns out that adding more platforms makes the solution easier. (Three is the hardest, and is the required minimum number of platforms). I also split the Start stacks and arranged them to require the most moves. The End Goal is still a single stack on the right platform, ordered by descending color number.

A simple thing to watch for above is that since the Blue Block is #1, it needs to be placed last, on top of the Solution Stack. Consequently, it frequently interfers with the progress of the higher numbered blocks and has to "get out of the way." This is a more robust demonstration of the DECONSTRUCTION-type moves identified by Sussman's Anomaly.

You can leave thoughtful comments or questions at the link below.

1. "On the Complexity of Blocks-World Planning" Gupta, N.; Nau, D. - 1992"Given a starting Blocks World, an ending Blocks World, and an integer L > 0, is there a way to move the blocks to change the starting position to the ending position with L or less steps? This decision problem is NP-hard"

2. The legend of the "Sacred Tower of Brahma" is the same puzzle utilizing 64 starting discs rather than 3. The increased number of disks does not change the solution strategy, however, the time requirement is unexpected — completing the Tower is said to "bring about the end of the world." Shifting 64 disks at one second per move would require 264-1 seconds, or roughly 42 times the estimated age of the universe. So actually the world ends before the puzzle can be completed.