Illusion of Thinking

One Puzzle to Rule Them All

December, 2025

In June of 2025, scientists in Apple's Machine Learning Research group published a paper evaluating the current crop of LRMs (Large Reasoning Models). Their LLM counterparts had long been accused of merely being "Stochastic Parrots" with no ability to reason through even simple puzzles. If ChatGPT appeared to solve a puzzle when requested, it was merely regurgitating a solution humans had previously published on the internet. LRMs claim to use a different architecture that "reasons" through scenarios, similar to how human problem solvers operate. Apple's paper disputes this claim for LRMs, and concludes by "ultimately raising crucial questions about their true reasoning capabilities.1"

The Apple scientists picked four canonical reasoning puzzles to test LRM performance: 'Tower of Hanoi', 'Checker Jumping', 'River Crossing', and 'Blocks World." The puzzles are similar in that they all utilize relatively simple solution patterns that can be repeated to solve variations with many initial pieces. For example, the 'Tower of Hanoi' puzzle can be optimally solved with 2n-1 moves. This means the simplest variation with three disks can be solved in seven moves, while solving the puzzle with the legendary 64 "golden disks" would take over 500 billion years2! But if you had the time, the process would be the same.

If given the number of disks that would appear in a tutorial on solving the Tower of Hanoi puzzle, say 3 to 5 disks, the LRMs perform accurately, but beyond a reasonable threshold, they fail completely. For the other style puzzles with fewer published tutorials, the LRMs fail even more quickly. This indicates the LRMs are not actually discovering rules through a reasoning process; rules would not degrade with repeated application.

I have little doubt that the effect of the Apple paper will be to have LRMs receive additional training on these specific puzzle failures, thereby perpetuating the "Illusion of Thinking." A more interesting outcome would be using the 'Tower of Hanoi' puzzle as a type of benchmark. As mentioned in the conclusion of my article on "ARCHIE," being able to solve this problem represents a benchmark for automating abstract reasoning.

The Historical Divide

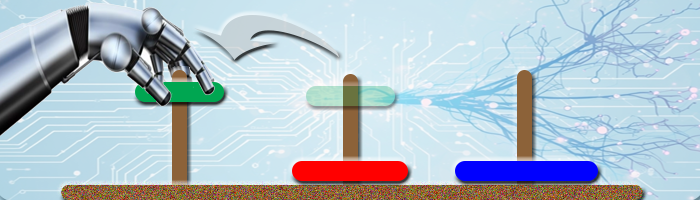

The introduction to my article "Kingdom of Mind" highlights a fundamental split in the search for 'Mechanized Intelligence' that emerged soon after computers became involved. Graphically, it looks something like this:

The path on the right, which attempts to artificially create intelligence by simulating a brain, was not originally considered "AI." The left side, which approached intelligence by modeling the functions of the human mind, was considered the only valid type of "AI" at that time. But anyone talking about "AI" today will almost certainly mean the brain-inspired artificial neural networks.

If we consider a good benchmark for artificial reasoning, it is interesting to note that the "General Problem Solver" from 1957 could legitimately solve the "The Tower of Hanoi" problem. Conversely, the Apple paper calls into question whether a pure Artificial Neural Network ever will.

Rules of the Game

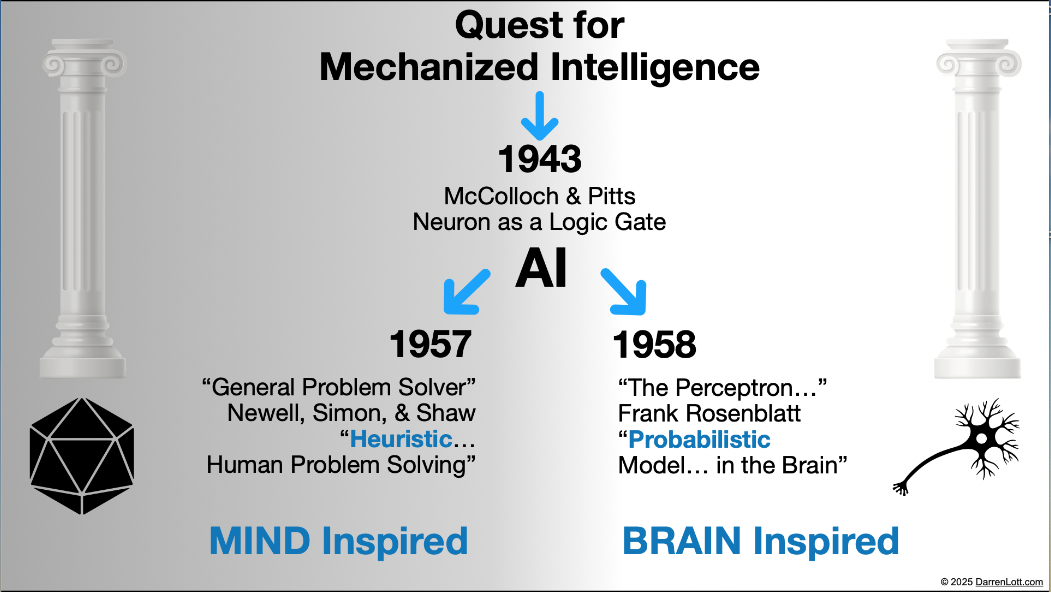

Let's take a quick look at how a human would approach solving this puzzle.

Friendly skeptics of the 'Mind' approach to AI will say that if a puzzle requires 'programming' to be solved, then it isn't really demonstrating reasoning or intelligence. The notion that any kind intelligence will just 'learn' how to solve a puzzle like this is naive. In the graphic above, I am already giving you some instructions with the labels 'Start' and 'Goal.' But even that is not enough. Your own intelligence will require some more "programming" in the form of examples and instructions.

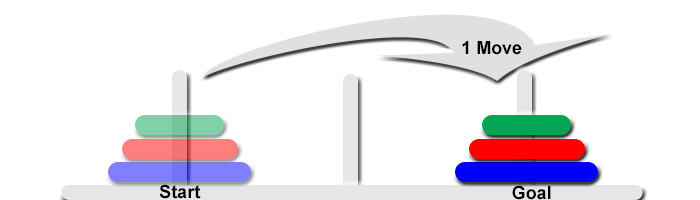

The first capability you need is to recognize the objects (3 colored disks) that have to be moved from the start to the finish. You also have to be capable of performing the action MOVE. If you already have the necessary skills you would move the stack of disks from the 'Start' to the 'Goal' position all at once. But this would be a failure, since there are more requirements.

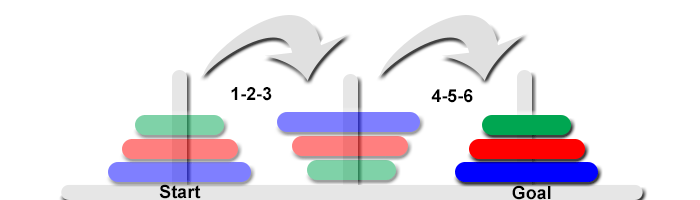

The next instruction is that the 'disks can only be moved one at a time'. This changes your single-move strategy to now requiring six moves. You also have to know how the disks separate and also recognize that moving them from the 'Start' peg directly to the 'Goal' peg would result in an inverted stack (failure). So you will also need to recognize that the first stack transfer (one at a time) results in an inversion and a second stack reposition (one at a time) reverses the reverse-order. With this strategy, the 'World Ending' 64 golden disks would only require 64 + 64 moves. So it can't be that simple.

The last INSTRUCTION required to solve the Tower of Hanoi puzzle is that 'a smaller disk cannot be placed over a larger disk.' This final requirement makes all the difference in the world (literally). So you need to begin by moving the small green disk to an open position, and then the only viable move is to move the medium red disk to another open position. Your own intelligence needs to kick in at this point, determining the ordered moves to reach the 'Goal'.

Our Friend ARCHIE

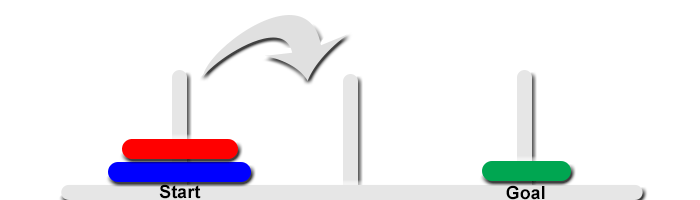

My claim is that ARCHIE uses the strategy of 'MIND INSPIRED' AI, following in the footsteps of programs such as the General Problem Solver (GPS). GPS was a RAND-funded program that could solve the "Tower of Hanoi" puzzle back in 1957. ARCHIE was created to solve ARC-type puzzles, which have strong constraints that seemingly prevent solving many-step challenges, like the Tower. ARC puzzles have several static Input/Output examples, and then only an Input as the test. If ARCHIE recognized a 'Tower of Hanoi' pattern in the examples and then just produced a 'Single-Move' solution, that would not be the same as solving the puzzle. What type of progress could ARCHIE make given the limitations of the ARC puzzle domain?

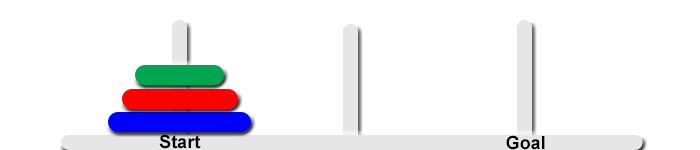

This would be the correct Output solution under the strict ARC Puzzle paradigm, but it is not demonstrative that any of the solution steps were followed.

I was not sure how the "Rules" for solving the Tower puzzle could be communicated to ARCHIE following the existing ARC format and programming. That was the challenge. Given the 30x30-pixel and 10 color limitation of the ARC puzzles, this helped me define the number and spacing of the disks. The disks center on three platforms instead of pegs, which means the narrowest disk (green above) could be two wide.

The next limitation in comparing ARC puzzles with "steps" in the Tower challenge is that all the ARC Input/Output examples are "stateless" and stand alone. Each move in the Tower puzzle depends on the previous move, especially since the goal is an optimal straight sequence of moves from start to finish. But how to introduce a "memory of state" with just a few Input/Output example images?

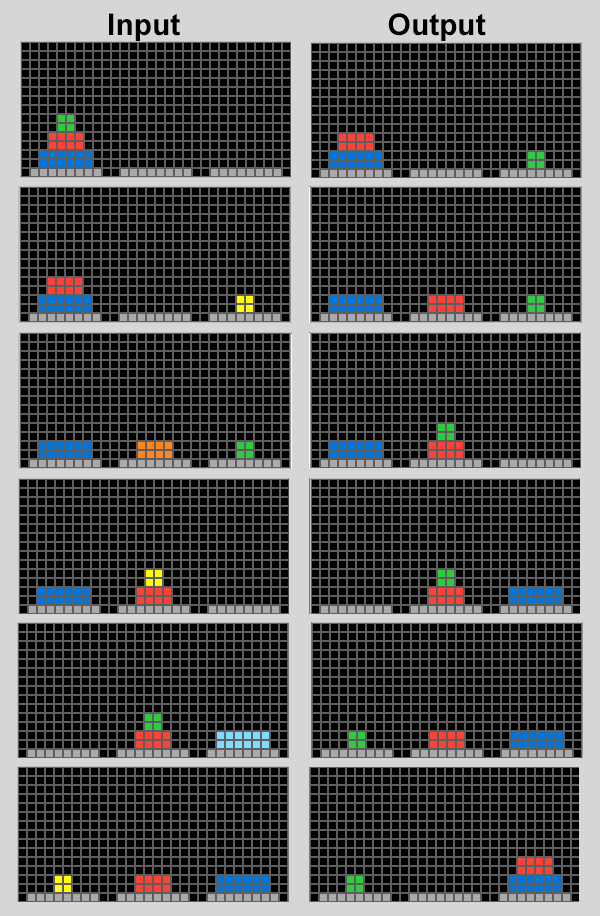

The Input/Output examples above follow all the ARC Challenge conventions, but I have them in order so you can see the optimal sequence. ARCHIE can observe the pairs in any order. The extra "trick" I added is that the last disk that moved has changed color on the next Input and will have to be changed back on the Output. What ARCHIE figures out on its own is that Yellow->Green; Orange->Red; Teal->Blue; and that an Object has MOVED.

For details on HOW ARCHIE WORKS, consult Part Two of the original article. From a logical perspective, ARCHIE uses three-stage reasoning:

- Abduction: This is the "Sherlock Holmes" method of forming a likely conclusion from a select set of observations. ARCHIE analyzes changes in the Objects it detects and proposes Actions to account for the difference.

- Induction: Summarizing all of the Actions in the given Examples, ARCHIE then compares the Attributes of the Objects in search of consensus. Rules are applied if they are not contradicted by any of the Action-Attribute associations in the Examples and Test Input.

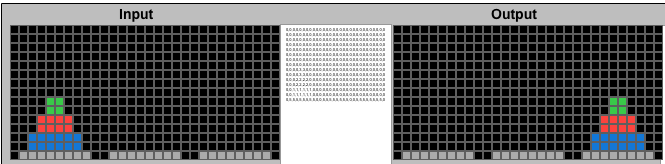

- Deduction: Finally, configured Actions and required Attributes are applied as a set of Rules, in order, to the Objects detected in the Test Input image. From the image pairs above, ARCHIE comes up with the following Rule set:

[TOWER]| pHeight:2

[PAINT,2,2,2,Void]| pCount:8| pHeight:2| pWidth:4| Color:Orange

[PAINT,1,1,1,Void]| pCount:12| pHeight:2| pWidth:6| Color:Teal| nSize:Largest

[PAINT,3,3,3,Void]| pCount:4| pHeight:2| pWidth:2| Color:Yellow| nColorFreq:Least| nSize:Smallest

In the "untrained" first pass ARCHIE took at these images, the [TOWER] Action was originally a [MOVE] Action. The full MOVE command is [MOVE,rotation,rows,columns,{duplicate/erase}].

Significant flexibility comes from the type of values that can populate these parameters. For example, "rows" can be an integer of rows to move up or down, the individual numeric attribute of the Object (like height), or a variable that will move all the way to the Border of the Image or move until it collides with another Object. That's a lot of flexibility! ARCHIE tried to use the MOVE command based on the Example image movements.

The problem is that a single value, even a referential variable, won't work for how the Tower disks move each time. Sometimes they move left, right, up, or down. The Action would need to look something like [MOVE, r0, Tower, Tower, E]. The MOVE action would need to specify the row and column integers to position the moving disk correctly. The approach I took instead was to create a new action [TOWER] that populates the integer values of a [MOVE] command. Then it only needs to call the existing MOVE function. Far more code modularity!

The new instructions ARCHIE needed to solve the Tower puzzle are the same exact instructions a person needs: Move only one new disk each time. A larger disc cannot be placed over a smaller one. [TOWER] gives the row and column coordinates so the disk lands in the right place. The [PAINT] action is something ARCHIE already knew to perform.

The Rule Set ARCHIE generates works with ANY of the Input grids to produce the next required Output. Take any of the Input images from of the Examples, and ARCHIE produces the correct Output, even though it has never seen it (ARCHIE maintains no puzzle memory). This should mean that, given any starting position in the Tower puzzle, ARCHIE could continue forward to completion. But how to demonstrate this?

The Iterative Approach to Problem Solving

The ARC challenge format provides a single-step solution after comparing multiple similar examples. Solving the Tower of Hanoi is really a many-step process, with a single optimal move available at each step. If ARCHIE could feed its Output solution grid back into the next Input challenge, it should be able to complete the puzzle using the same steps a human would use. Adding an "Iteration" button enables this.

Iterative Solution for the Tower of Hanoi problem. Each Output is checked, and if it does not match the Final Solution, it becomes the Input to the next iteration.

A New Frontier?

The Iterative approach can be applied to any of the ARC Puzzles. Since they are solved in a single step, it's not an interesting addition on its own, but it does open up a new class of problems ARCHIE can solve. Adding more disks would be interesting, but the ARC 30x30 grid is limiting. Are there other similar puzzles that would fit elegantly into this format? (Please leave ideas in the Comments below.)

You can leave thoughtful comments or questions at the link below.

1. "The Illusion of Thinking: Understanding the Strengths and Limitations of Reasoning Models via the Lens of Problem Complexity" arXiv Paper - June 2025

2. The legend of the "Sacred Tower of Brahma" is the same puzzle utilizing 64 starting discs rather than 3. The increased number of disks does not change the solution strategy, however, the time requirement is unexpected — completing the Tower is said to "bring about the end of the world." Shifting 64 disks at one second per move would require 264-1 seconds, or roughly 42 times the estimated age of the universe. So actually the world ends before the puzzle can be completed.