Kingdom of Mind

Path to AGI ends in a Cornfield

October, 2025

In 1956, the pioneers of Artificial Intelligence declared machines would be able to use language, form abstract concepts, and solve the kinds of problems reserved for humans. And they thought significant progress could be made in 2 months by 10 hand-picked experts1. Two of these hand picked experts, John McCarthy and Marvin Minsky, went on to initiate an Artificial Intelligence lab at MIT2. They were among the first, but not the last, scientists to grossly underestimate the effort involved, and to provide hilarious predictions of sentient machines "just around the corner."

By 1957-58, the seeds for the greatest division in AI had already been sewn: Symbolic AI, as exemplified by Newell and Simon's General Problem Solver (1957), and Probabilistic AI as exemplified by Papert's Perceptrons (1958) (later marketed as Artificial Neural Networks). By the 1980s, the Symbolic AI movement had stalled, and after a very late start, Probabilistic AI has also stalled. Over half a century later, neither approach have even provided definitions for their highest goals: Intelligence and Consciousness. By the end of this article, I will tackle defining both.

The Turing Test

One of the earliest and most notable predictions about the eventual human-like abilities of machines came from Alan Turing in 1950.

Turing's prediction about the year 2001 was comparatively modest. The term AI had not yet been coined, and Alan's conjecture is merely about machines "thinking" 50 years in the future. This is a far cry from predicting a conscious, malevolent, artificial super intelligence (ASI). We will get to that prediction soon enough.

Turing's benchmark for testing if a machine can think was his proposed "Imitation Game." In this "parlor-type" game, a man and a woman would be segregated from an interrogator who submits written questions to them. The goal of the woman is to be perceived as a woman. The goal of the man is to submit answers to the interrogator such that he would be fooled into thinking the man was a woman. So Turing's "imitation game" is — can a man trick another man into thinking he is a woman? (The language in the paper is unambiguously gender specific.) Turing then proposes that the role of the trickster be taken by a machine, which attempts to imitate the man. If the machine can fool the interrogator 30% of the time, the point about "thinking" would be considered proven.

In 2001, a chatbot named Eugene Goostman supposedly beat the Turing test by pretending to be a 13-year-old boy from Ukraine. There were mitigating factors to influence this positive result, but the year 2001 is notable.

By 2025, GPT-4.5 was being identified as human 73% (more often than the actual human counterparts) in randomized, controlled Turing tests. We have a Winner! Interestingly, ELIZA (invented in 1966) was included in the contest and scored 23%, worse than the humans, but ELIZA outperformed GPT-4o's 21% score.

I think it's important to note, again, that Turing is proposing a test of "thinking" and not "intelligence" or "consciousness." The test is a purely language-based performance. It's also an "Imitation Game" and winning may not mean what some want it to mean. Over text, fooling another man that you are a woman does not make you a woman. Over text, fooling human intelligence does not make the computer intelligent.

2001: A Bolder Prediction

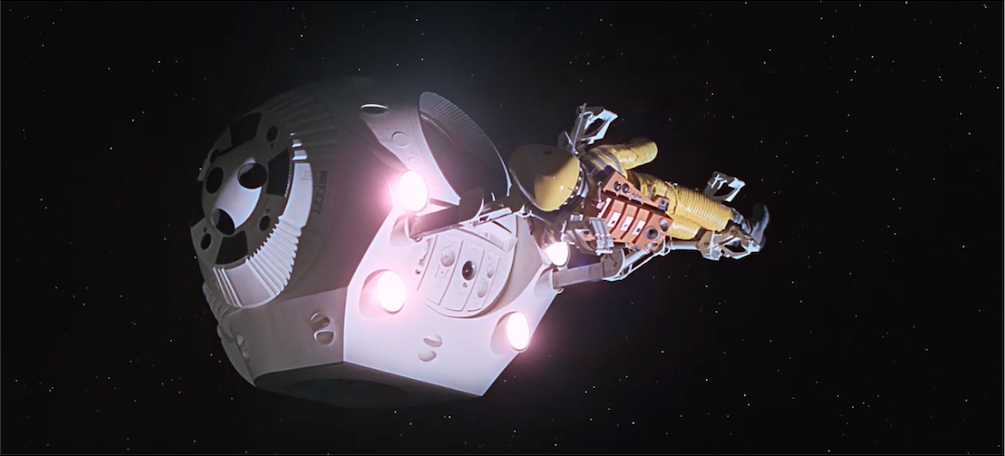

Stanley Kubrick, the director of 2001: A Space Odyssey, was fanatic about scientific accuracy for his 1968 film and hired many consultants. One of these was Marvin Minsky from the MIT AI Lab.

You might expect that HAL 9000, a sentient AI that becomes paranoid and murders the crew, was Minsky's contribution. It wasn't. Instead, Kubrick asked, "By 2001, do you expect that computers will be able to speak coherently?" To this, Minsky replied, "By that time their voices will be very good and nicely articulated, but I doubt they'll understand what they're saying." This turned out to be prescient and redemptive of the exuberance characteristic of a decade before. But it didn't deter Kubrick's vision for HAL.

What Minsky did contribute to the final movie was inspiration for the design of the EVA Pod. ("Open the Pod bay doors, HAL...")

Right here, we see the foundational split in AI, and Marvin Minsky is central to it.

I'm Sorry Dave... I'm Afraid I Can't Fund That.

In the 1960s, Marvin began designing and programming "The Minsky [robotic] Arm" to build things with blocks, a skill with which most children are adept. These challenges colored Minsky's work for the next 60 years. In 1986, he wrote The Society of Mind, which extensively uses "The World of Blocks" as illustrative. In 2011, he conducted a 26-hour MIT graduate course, surveying the state of Artificial Intelligence (MIT OpenCourseWare: The Society of Mind). Robotics examples are still front and center, and in the concluding lecture, he challenges the graduate students to think about "how to make machines smarter." As former president of the American Association for Artificial Intelligence, it's telling that Professor Minsky asks about "smarter machines" (like the EVA Pod) and not about an emergent super intelligence (like HAL 9000).

During the lectures, Minsky expresses disdain and frustration with probabilistic approaches to AI. He also warns the students against using neuroscience as a guide to design. When asked about the "lack of progress" in AI, he says it stalled in the 80s because all the funding has gone into artificial neural networks, leaving only about 12 people worldwide to do the required work of deciphering common sense reasoning.

Moravec's Paradox

"In attempting to make our robot work, we found that many everyday problems were much more complicated than the sorts of problems, puzzles, and games adults consider hard."

"It was this body of experience, more than anything we'd learned about psychology, that led us to many ideas about societies of mind."

—Marvin Minsky, from The Society of Mind, 1986

Aside from monetary challenges, one of the biggest impediments to advancing artificial intelligence is labeled "Moravec's Paradox." It was named for Hans Moravec, who wrote a 40-page essay on the subject in 1976. A phrase capturing the essence of the paradox was popularized by Steven Pinker:

Moravec's "Raw Power in Intelligence" essay asserts that the division between the easy things and the hard things is based on the timeline of evolution. Things that are hard for a computer are essential to living organisms, and so natural selection has had millions of years to work out solutions. These solutions are instinctual and seem "free" or easy. The seemingly "hard things" are recent man-made problems and don't have biologically prepared solutions. So they seem hard by comparison, but really are not.

Catching a ball is easy for a child, a monkey, or a dog. But playing chess is not. The easy task is handled by highly evolved sensory and motor portions of the brain. The hard task requires reasoning and awareness.

Like Minsky, Moravec believes that creating a path to intelligent machines is an engineering problem, and "can be solved by incremental improvements and occasional insights into sub-problems." These sub-problems, in the parlance of "Society of Mind," are called agents, and Minsky writes, “you can build a mind from many of [these] little parts. When we join these agents in societies—in certain very special ways—this leads to true intelligence."

The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind

Above is the title of a 1976 popular science book by Princeton psychologist Julian Jaynes. I add "Breakdown" to question "consciousness" as the pinnacle achievement of an intelligent mind.

"But there can be no progress in the science of consciousness until careful distinctions have been made between what is introspectable and all the hosts of other neural abilities we have come to call cognition. Consciousness is not the same as cognition and should be sharply distinguished from it."

—Julian Jaynes, The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind

Jaynes's position is that human consciousness is unique, a by-product of language, and has manifested only in the last few thousand years. That's fun, but I am not buying into it. What is more interesting, though, is that Jaynes (then necessarily) posits an older "non-conscious" human mentality, prevalent for the vast portion of history. We will revisit that conjecture shortly.

In PART TWO, I will provide a working definition of Intelligence, plus reveal how "consciousness" is actually an Illusion.

1. A detailed history of this period can be found at Sean Manion's comprehensive MIINA Series.

2. The MIT Computer Science group merged with the Artificial Intelligence Lab and is still in operation as CSAIL.