Kingdom of Mind PART TWO

Path to AGI ends in a Cornfield

October, 2025

Previously on Kingdom of Mind...

In Part One, we identified two conspicuously missing definitions: Intelligence and Consciousness. Alan Turing introduced his "Imitation Game," hoping to demonstrate that machines "think." But there are several steps further to arrive at intelligence and especially consciousness.

What is Intelligence?

The current method for defining intelligence has mainly been listing a collection of purported capabilities. In 1997, a total of 52 professors with expertise in intelligence signed an editorial that defined intelligence as “the ability to reason, plan, solve problems, think abstractly, comprehend complex ideas, learn quickly, and learn from experience” (Gottfredson, 1997, p. 13)1. This definition supposedly captures what they considered biological intelligence, but that's just another list! In 1961, Marvin Minsky defined Artificial Intelligence as “the ability of machines to perform tasks that typically require human intelligence.” That seems circular, but he was trying to establish a connection for "Artificial" to Human. In 2019, Françios Chollet, creator of the ARC prize, defined the intelligence of a system as “a measure of its skill-acquisition efficiency over a scope of tasks, with respect to priors, experience, and generalization difficulty.” I feel all these definitions essentially fall back to "like great art, or pornography, I just know intelligence when I see it."

A Working Definition, Finally

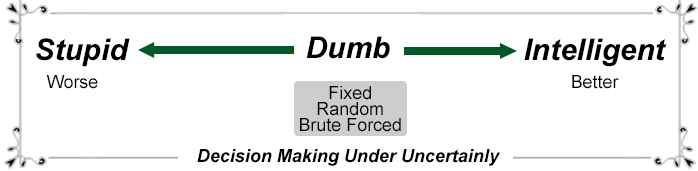

If we can't satisfactorily define intelligence, perhaps we should ask a related question. What is Stupidity?

This might seem like an unusual approach, but asking ourselves, what makes something worthy to be called stupid? What things do we consider stupid? A bottle of water is not stupid, nor is it intelligent. The proper term would be "dumb." It's not succeeding or failing, it's just not participating. It helps us realize that stupidity requires a failure at being intelligent.

So with "stupid" at one end, "dumb" in the middle, and "intelligent" as the capper, we now have a scale with which to work. If the scale represents success in"decision making under uncertainty," we can even find ways to quantify the classification of what makes something "intelligent."

Suppose we select the task of predicting the outcome of an event for our model. Prediction is a good example of decision-making under uncertainty. Let's say the event is predicting the flip of an apparently fair coin. The "dumb" system (in the middle) is fixed at always predicting "heads" and is right 50% of the time. The "intelligent" system, in this example, mixes heads and tails predictions. It reliably "beats the odds" and is right 70% of the time. The "stupid" system is consistently wrong, correctly predicting outcomes only 25% of the time. The "stupid" system performs worse than chance, worse than making no decision at all. So our simplified definition features an intelligent system performing better than chance and a stupid system performing worse than chance. Dumb is in the middle.

"Decision making under uncertainty" is not limited to coin flips or probability exercises. Let's check a few other examples: A thermometer is representative of temperature, but is not making even a primitive decision when the mercury expands in the tube. A mechanical thermostat is closer to intelligence, turning on cooling when a high temperature is reached and heating when a cold temperature is reached. It could be argued that this action represents a basic form of decision-making, but alas, the decision is not made under uncertainty. A thermostat is not intelligent. However, if the thermostat included some predictive mechanism, anticipating fluctuations in the real world and acting before each set point, that would seem like the basis for a mechanical intelligence. If this device were misconfigured, fluctuating wildly, turning cooling on long after it was already too cold, we would call it "that stupid thermostat!" So it seems for a system to be deemed intelligent, it also requires the possibility of being stupid.

Given the chance to bet along with the systems in the coin flip example, most people would throw in with the "intelligent" system and it's 70% success rate. A clever psychologist might point out this was another example of "irrational behavior" since betting against the "stupid system" would provide an even more favorable, 75% success rate. It's irrational to "leave the extra 5% on the table," they might say.

Tribal Tribulations

A modified model helps explain why contrary betting is not an obvious choice. Because in the physical world, that opportunity rarely exists.

Let's apply this model to a hunter/gatherer tribe and see where we would cast our allegiance. The task is for three small subgroups to go out, find food, and bring it back to feed members of the tribe. All three groups depart and return 3 days later.

The intelligent group says, "We remembered an area by the stream that had immature berry bushes and some antelope nearby. When we arrived, the bushes were now full of berries, and an antelope was eating the leaves. We killed the antelope, brought back its meat, and also a large basket of berries. Enjoy!"

The dumb group says, "We just went back to where we picked all the berries last time, but there were only a few left. We ran low on water and had to eat all the berries we found. At least no one got lost. Sorry!"

The stupid group says, "We crossed the river to the other tribe's berry patch. There were a lot of berries, and when we were picking them, a warrior from the other tribe arrived and stabbed one of us. We killed that warrior, but then we heard others coming. We dropped all the berries and had to leave the wounded behind. The other tribe followed us back across the river. Run!"

What I hope this cartoonish story provides is a reason for why we align with success and just avoid stupidity. Rarely can we take a contrary position against stupidity and benefit1.

Sticks and Stones

"Better to keep one's mouth shut and thought stupid, than open it and remove all doubt."

—Mark Twain, Abraham Lincoln, The Bible, etc.

This phrase (variously attributed) seems to capture the idea of a non-participating "dumb" center that can descend to "stupid" by a failed attempt at intelligence. The term "dumb" has an interesting history, and until the 19th century primarily referred to "speechless." A "dumbwaiter" was a small household elevator used to bring food up from the kitchen without talking or listening to private conversations. "Dumb animals" is a reference to their lack of (human) language. "Dumb Brute" captures the unintelligent user of "Brute Force."

Hellen Keller was "deaf, dumb, and blind," but no one today would consider her "stupid." It was unfortunate that accusations of stupidity would overshadow a more specific meaning of "non-language-processing." A revamped quote might be:

"Better to keep one's mouth shut and thought dumb, than open it to reveal stupidity."

The example of speaking foolishly, not speaking, or speaking wisely might seem to break the requirement of decision-making under uncertainty. However, speaking foolishly or wisely is actually declaring a future decision-making strategy. Advice about future action is advice about future decisions.

Alan Turing's "Dumb Puzzle"

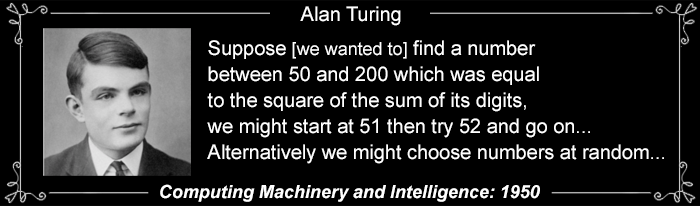

The same paper in which Alan Turing introduces "The Imitation Game" concludes about 30 pages later with a math puzzle:

Turing does not provide an answer or even challenge readers to try to solve it themselves. Instead, he uses his concluding paragraphs to extol the virtues of using the "random method" over the "systematic method." He notes this method would be "analogous to the process of evolution." I will identify his "systematic method" as "brute force" — simply try every possible solution without reducing the number of possibilities through reasoning.

Within a paper on Intelligence, I find the omission of "reason" as a strategy, glaring and disturbing. Is it possible that reasoning about this problem won't yield a solution superior to Turing's Brute Force or the Random Search methods?

No! Turing is providing a false choice that strikes me as "stupid," but in fairness, just provides two more ways to be "dumb": Brute Force and Random Selection.

Let's try an INTELLIGENT analysis of this puzzle instead:

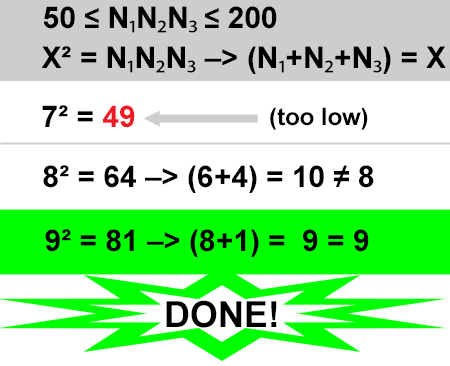

The first thing we need to do is REASON about what is being asked. The answer is not going to require algebra or fancy math skills. We know the answer will be a number between 50 and 200. We are going to add the digits of the proposed solution together to get another number, the sum. As an example, 51 would sum to (5+1) = 6, and 199 would sum to 19. As the final condition of the puzzle, the sum value is the square root of the original number (between 50 and 200). Seems like it could require some sophisticated algebra. But it won't!

OK.

Instead of calculating the square roots of the sums of the digits for all the possibilities, let's flip it around. Offhand, do we know a squared number near the bottom of the range? Yes. 72 is 49.

49 is just below the lowest valid answer (50 to 200), and the fact that we are adding the digits of each number means the answer will be an integer. So we can jump through a few integers larger than 7 and see what happens. 82 is 64, and (6+4)= 10, so that's not it. 92 is 81, and (8+1)= 9 and BINGO!

This "heuristic method" wildly outperforms brute force, which itself outperforms random guesses. This is an intelligent solution2.

I could have come up with my own puzzle to demonstrate the limits of dumb methods. In fact, my article Traveling Salesman Problem outlines techniques that bypass the limitation of brute force

and The Numbers discusses how prime numbers are NOT random.

In this seminal paper on Intelligence, was Turing's conclusion reverse psychology? Did he present this puzzle, falsely bracketed by two "dumb" methods, so the reader would see "intelligence" by it's very omission?

I don't think so. But if that was his intent, it didn't work, and we are left with a bitter lesson.

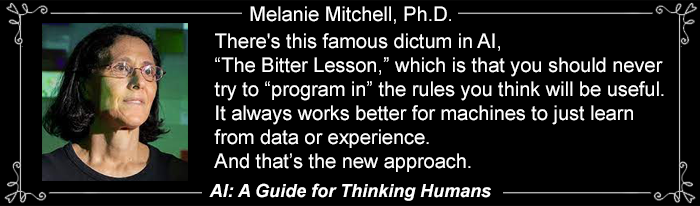

The Bitter Lesson

"We have to learn the bitter lesson that building in how we think we think does not work in the long run."

— Rich Sutton

In a recent Medium article, Melanie Mitchell brought up "The Bitter Lesson." I looked into it, and the Bitter Lesson is far worse than I ever expected. It's not merely that Rich Sutton expressed this particular opinion, but rather that it has been embraced as gospel. This is what future generations of (would have been) problem solvers are being indoctrinated with: "The human-knowledge approach tends to complicate methods in ways that make them less suited to taking advantage of general methods leveraging computation3." By "methods," Sutton is directly referring to "Deep learning methods [that] rely even less on human knowledge, and use even more computation, together with learning on huge training sets." This is why, 6 years later, Microsoft is reactivating the Three Mile Island Nuclear Plant just to power their AI data center.

The reason the AI community can't define "Intelligence" is because they are hostile to human intelligence, demanding adherence to the "Dumb, Brute Force" approach. Very clearly, big tech wants to displace human thinking with a "Colossus" or "HAL 9000" superintelligence. I don't think massively scaling DUMB will ever leapfrog INTELLIGENCE via spontaneous "emergence." But they do think that. — "because complexity!"

"Better to use our brute force compute and get equity, than attempt something intelligent and get fired."

Don't Build the Torment Nexus

In 2021 Alex Blechman created a humorous tweet:

Sci-Fi Author: In my book, I invented the Torment Nexus as a cautionary tale

Tech Company: At long last, we have created the Torment Nexus from the classic sci-fi novel Don't Create the Torment Nexus

Now that we have a working model of Intelligence, we can see that the people building the Torment Nexus are intentionally basing it on DUMB. And they are openly hostile to human intelligence. Given how the scale works, is it more likely that a beneficent superintelligence will emerge, or flaws in its execution will STUPIDLY bring forth horrors at an unimaginable scale?

In PART THREE, we will discuss why consciousness is another property that won't emerge spontaneously, and why we shouldn't want it to, because "consciousness" is actually an Illusion.

1. Aligning with the strong against the week is not the same thing.

2. In discussing this puzzle Turing also suggests, "Since there is probably a very large number of satisfactory solutions the random method seems to be better than the systematic." We can easily test this with the heuristic above and see that 142 is the last square to check (142=196) and 102, 112, 122, and 132 also don't satisfy the puzzle criteria. So, NO. There isn't a large number of satisfactory solutions.

3. Full text (single page) of Rich Sutton's 2019 blog post by can be found here:The Bitter Lesson